This paper is written by Desiree McCray for Prof. Mark Taylor for the course Incarnation and Incarcerated Bodies on May 4, 2019 at Princeton Theological Seminary.

“Continue to remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison and those who are mistreated as if you yourselves were suffering.”

[Hebrews 13: 3]

In the United States, the Prison Policy Initiative estimated that more than 2.2 million people were incarcerated in the year 2016 (Walmsey 1). Those behind bars encounter tremendous suffering, fixed to the extremes of violence, isolation, and poor living conditions. As a result, within our theological discourse, the permanence of such forms of inequality and injustice like mass incarceration raises important questions concerning the problem of human suffering. Is a liberating theology of the cross possible or even valuable in review of those incarcerated? How can we move beyond a dialectical application of theologies of the cross to tangible methodologies that conjure resistance and hope?

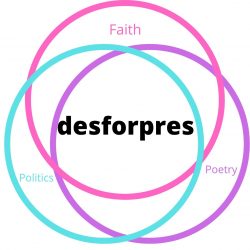

In Douglas John Hall’s book Lighten Our Darkness: Towards an Indigenous Theology of the Cross, the author articulates the shortcomings and potential failures of America and America’s “officially optimistic religion”. In Executed God: way of the cross in Lockdown America by Professor Mark Taylor, he presents a resistance of United States Lockdown and empire. In these works, a Christology of suffering may be critiqued to reject the automatic positivism and triumphalism associated with Christianity in the wake of gross indifference to the societal sin of the prison industrial complex. In this paper, I will argue that a Christology of suffering in the context of incarceration must be qualified not only through mere endurance through trials and tribulations, but through three key movements. First, I seek to revitalize narratives of Jesus as the suffering servant, then to reimagine the salvific work of atonement, and finally, to demythologize the triumph of Jesus on the cross.

First, According to Latin American liberation theologian Jon Sobrino,

“The cross is the outcome of an incarnation situated in a world of sin that is revealed to be a power working against the God of Jesus”

(232).

I suggest that this power referenced by Sobrino is not meant to oppress people but to free people. The Gospel Message is liberation, a release of the prisoner. Nevertheless, Jesus, a political prisoner, hung his head and died, nailed to a Roman cross. Thus, before we move toward empowerment, we must leverage the brokenness of God’s crucifixion. The Roman cross emblematizes an empire and much like Rome, the United States of America has risen to imperial status at the expense of the marginalized, namely incarcerated peoples.

In the backdrop of empire, the death and suffering of Jesus, has unique visibility within Christian history while the horrors of Jesus’ state-sanctioned, excruciating execution faces a level of erasure by the believing masses. Hall writes “Middle America has long been meeting the Resurrected’… a still risen, triumphant, and eminently positive Jesus” (140). Christians love to witness the pre-crucified Jesus, who performed miracles and healings. Christians celebrate the post-crucifixion Jesus who claimed victory over every evil, death, and the grave. However, I suppose that as a faith, Christianity deals poorly with the implications oframifications of suffering by the marginalized, the dispossessed, and underclass. In order to leverage resistance and hope, the first act of resistance precipitates moving towards dwelling in the pain of incarceration and not moving past it to offer easy, yet nonoperative hope. We must meet the suffering savior and redeploy Jesus as “the Suffering Servant”, as one who encountered the depth of human agony to the utmost. Hall signifies in Lighten our Darkness:

“It is nothing short of blasphemy and sacrilege that the Christ encountered by Middle Americans in their ‘sanctuaries’ is a bland, sweetly Aryan, unblemished, and triumphant Jesus”

(141).

Until we can meet the “mutilated, sorrowful, forsaken” Christ of Galilee, we will only continue to deny the suffering of many of our citizens of the United States who find themselves behind bars (143). There is no hope in denial.

Such a view of Christ as “Suffering Servant” introduced by the late black liberation theologian James Cone identifies a categorical operation within theodicy in which the “God of the Oppressed” empowers us to oppose injustice. Theodicy particularly maintains the question “How can God be an all-powerful and all-good God and allow such suffering to take place in the world?” Christology that mitigates Jesus’s suffering and fast forwards past the his pain degrades the necessity of the gospel. Cone pathologized the problem,

“The cross of Jesus is God invading the human situation as the Elected One who takes Israel’s place as the Suffering Servant and thus reveals the divine willingness to suffer in order that humanity might be fully liberated”

(Cone 124)

If we turned a blind eye to suffering, we fail to truly capture what we are up against and what is truly at stake. According to Taylor, an “adversarial politics” gains traction toward resistance when we account for the complexities of Jesus who suffered in the “theatre of Galilee”, a socio-political location of imperial domination (208). Failure to name our opposition and take on an adversarial politics jeopardizes our effective response to mass incarceration. It would be akin to fighting blindfolded.

Second, Blindness has infiltrated our understanding of our own salvation, too. In order to have a truly liberating Christology of the cross we must reimagine the work of atonement. Most evangelical Christians will explain to you that Jesus’s death on the cross acted as a substitution and that Jesus paid the penalty for our sins. We deserved death, but because of Jesus we do not have to suffer true death, eternal damnation. Jesus’ death won the victory and we can shout with joy the scripture:

“O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?”

I Corinthians 15: 55

However according to Cone, this narrow orthodox “has become a form of cheap grace… an easy way to salvation” (9). Beyond victory, there abides a resistant and abolitionist work to do. We must labor not in vain towards a Christology that champions orthodoxy more than orthopraxy. While those incarcerated face deep dehumanization and subordination, they feel a pain only they can know, and no one can stand in their place to reduce their earthly trauma. Overcoming, coping, and responding to our pain are our duties as human beings and the substitution atonement model seems to undermine personal suffering, making for the case that Jesus suffered so that we do not have to. Still, the eschatological hope that Jesus’ Parousia (second coming) will completely eradicate all suffering and evil is not enough for those that are behind bars now, seeking liberation now.

Many may claim that the salvific work of Christ has reached completion, yet as people of faith we wait in eschatological hope. I have heard preached from many pulpits that “Jesus paid it all.” To pay usually infer the meaning “to spend” but it can also imply suffering in the sense that people have to “pay” for their wrongdoing. As a result, Jesus suffered with us, for us, alongside us. We can reimagine his salvific work as not merely substitutionary but also as exemplary. Cone writes:

“There is no liberation without transformation, that is, without the struggle for freedom in this world”

(100).

Because Christ suffered, humans must suffer, too. The work continues and the struggle continues to contradict and subvert the current world order. Moreover, to reduce the cross to a merely salvific event is problematic because Jesus’ death on the cross occurred outside of a vacuum within history. Jesus’ death should lead us to ask questions about the truth of God and how the crucifixion affects God’s self (Sobrino 181). Reimagining the salvific work of Christ calls us into suffering with Christ to interrogate and wrestle with the very meaning beyond theoretical atonement. Reimagining requires us to know that with our hands and feet we build God’s kingdom, no longer rendering ourselves to some passive agent of social change. Likewise, Sobrino echoes “our contact with Christ is not to be experienced through primarily cultic adoration, but through the following in the day-by-day service of the kingdom” (308). An emphasis on cultic worship often leads to deemphasizing the praxis of direct action that leads to eradicating injustice and oppression. A hopeful Christology would acknowledge a need for a healthy quantity of dramatic action to initiate a social movement toward change.

Third, we must demythologize the triumphant narrative of the cross. The moment of the cross epitomizes human suffering. Suffering announces trouble in our souls that obstruct paths to peace and in the words of Copeland,

“[suffering is] the disturbance of our inner tranquility caused by physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual forces that we grasp as jeopardizing our lives, our very existence. Suffering while never identical with evil, is inseparable from it”

(Troupe 200).

The horror of the cross made the disciples run away (Mark 14: 50-52). Such suffering cannot be sidestepped by triumphalism because of Jesus’ resurrection. According to Hall, the gospel message indeed commands an understanding of victory, but here triumphalism versus triumph need to be distinguished (142). Triumphalism says that Jesus’ work on the cross is “officially positive” with little grey area to experience the nuances of his trauma. Hall writes “the real triumph can only be an object of faith, not of sight” (144). By this, Hall means that the true victory was that by faith Jesus and his disciples healed, took care of widows and the poor. They walked humbly, did justice, and loved kindness. We cannot simply seek to claim victory over societal sins without having faith. We must construct a faith that does not only believe but also does works of faith. James 2:26 reads, “For as the body without the spirit is dead, so faith without works is dead also.” Hope is lost when Christians can preach the gospel from a building but when they leave the building they walk past the poor, and they turn a blind eye to mass incarceration and minoritized individuals targeted by systems of oppression. Each church must account for its fruits.

In addition to critiquing triumphalism, we must consider a theology that does not assure us the security of happiness. The case of “winning” or sensationalizing consistently victorious narratives insults those who find themselves in conditions of incarceration. They may be asking why and how do I find myself “locked up” if I have a victory over sin and death? Hall suggests

“We must live as Christians under the cross without assuming a resurrection that is either logically or existentially necessary”

(145).

Mandating a resurrection in our social context outside of eschatology pushes away our hope because hope represents what we desire and expect. We should expect a resurrection without feeling that we must always accept our “crosses”. Resisting the notion of artificial triumph in exchange for the true triumph of faith undergirds Hall’s argument (Hall 146). There has been a false sense of triumphalism in the “glory” of God’s conquering of sin because sin still affects us today. If we expect a divine intervention from God but our situations do not change and we are not liberated, we lose hope if we choose complacency over resistance. For this reason, a triumphant Gospel should be preached not out of necessity to keep people deludedly optimistic, but rather the gospel of the cross should be preached out of the possibilities of the power of human faith, God’s goodness, and pursuit of liberation. This gospel should set the captives frees (Isaiah 61:1).

In conclusion, The United States as a nation imprisons more people than any other developed country (Walmsley 2). Christianity struggles to respond with a theology of the suffering of Jesus on the cross. Jesus, a prisoner of the state and as executed God enfleshed in an earthen vessel, presents us a challenge to erect a Christology that encapsulates the historical limitations of humanity, mixed with the limitlessness of an eternal, omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent God. We struggle to comprehend this image of God while proposing Jesus as exemplary model of suffering for all humanity, particularly the least of these. In this paper, I have reconstructed the possibilities of a hopeful and resistant Christology of suffering considering mass incarceration by offering three evaluations. First, I aimed to reclaim narratives of Jesus as the suffering servant. Second, I sought to rethink the theoretical project of redemption. Finally, I endeavored to reinterpret the triumphalism of Jesus’ mission on Calvary’s cross.

Works Cited

Cone, James. God of the Oppressed. Orbis Books, 1997.

Grimes, Katie. “‘But Do the Lord Care?’” Political Theology, vol. 15, no. 4, July 2014, pp. 326–352.

Hall, Douglas John. Lighten Our Darkness: toward an Indigenous Theology of the Cross. Academic Renewal Press, 2001.

Sobrino, Jon. Christology at the Crossroads: A Latin American Approach. Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2002.

Taylor, Mark Lewis. The Executed God: the Way of the Cross in Lockdown America. Fortress Press, 2015. Print.

Troupes, Carol. “Human Suffering in Black Theology.” Black Theology: An International Journal, vol. 9, no. 2, July 2011, pp. 199–222.

Walmsey, Roy. “World Prison Population List.” Prison Studies Organization, International Center of Prison Studies, 2017.